Understanding & Choosing Saltwater Fly Lines – A Fly Line Primer

By George Roberts

Arguably the most important piece of equipment in your fly angling arsenal is your fly line. This is the piece of your outfit primarily responsible for delivering your fly to the fish. While I’m not overly particular about the rods I fish with—they all work the same way, and the vast majority cast reasonably well—I’m very particular about my lines. The lion’s share of the money I spend on equipment is spent on fly lines.

Today’s manufacturers produce lines in a mind-boggling plethora of configurations. While having options is a good thing, the downside to such overabundance is that choosing a fly line can be difficult for the experienced fly angler as well as the novice. If you fish more than a few times a season you need to educate yourself about fly lines, as this selection of your equipment is too important to leave to the guy behind the counter—who may not know much about them himself.

In this article, I’ll present an overview of saltwater fly lines and how to choose one to match your particular rod, your game, and your casting ability. We’ll then take a look at how to cast the line most effectively. Finally, I’ll offer you a few tweaks you can make to your fly line—things I’ve learned over the last 30 years of fishing the salt—that will improve its overall performance.

A modern fly line is a length of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or similar plastic applied as a coating over a material core—most commonly braided multifilament nylon.

Every weight-forward line consists of two primary sections: the head section and the running line. The head contains all of the effective weight of the fly line and comprises four sections: the tip, front taper, belly, and rear taper.

Every weight-forward line consists of two primary sections: the head section and the running line. The head contains all of the effective weight of the fly line and comprises four sections: the tip, front taper, belly, and rear taper.

The tip is the relatively short section (usually no more than 12 inches) of small-diameter line to which you attach your leader. Each time a new leader is attached, a bit of the tip is sacrificed. Should you wish, you could remove the entire tip of the fly line without significantly altering the line’s performance.

The front taper of the line joins the belly to the tip, and is the section of line that determines how a fly will be delivered. In general, the more necessary it will be for the angler to make a delicate presentation, the longer the front taper will be—six feet or longer on some lines designed primarily for bonefish.

The belly (also called the body) is the relatively long section of large-diameter level line that makes up most of the weight of the head and supplies the cast with most of its energy.

The rear taper forms the transition from the belly section to the running line. The rear taper can be as short as three feet on some designs, or exceeding 20 feet on others.

The running line is the small-diameter level line that forms the remainder of a weight-forward line. The end of the running line attaches to your reel’s backing.

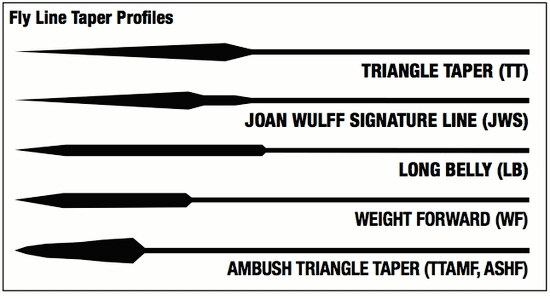

[Figure 1. The standard weight-forward fly line and the Wulff triangle taper fly line.]

This is the basic anatomy of a weight-forward fly line, though a number of manufacturers have taken liberties with the standard construct. For example, at least one company markets a fly line that includes a middle taper to front-load the weight of the belly with the idea of more easily turning over larger flies (I can’t speak to whether the line actually lives up to the claims).

The weight-forward design that deviates significantly from the above description is the Wulff triangle taper. Conceived and patented by the late Lee Wulff, the head of the triangle taper consists only of a continuous front taper (17 to 40 feet, depending on the particular model) backed by a three-foot rear taper, which transitions abruptly to the running line. Wulff’s idea was to create a fly line in which a heavier line was always turning over a lighter line for a very efficient transfer of energy throughout the cast. This line works particularly well for roll casting (which admittedly does not play a major part in saltwater angling). Once the front and rear taper get outside the rod tip, the triangle taper can be cast as any conventional weight-forward fly line.

Floating lines are best suited to use either in fairly short water columns (inches to 10 or so feet), or to fish for game that are feeding at or near the surface, regardless of the depth.

Floating lines are best suited to use either in fairly short water columns (inches to 10 or so feet), or to fish for game that are feeding at or near the surface, regardless of the depth.

Your targeted species, and where you’ll fish for it, will determine your choice of line density. Line densities fall into three broad categories: low density (floating lines), intermediate density (intermediate lines), and high density (sinking lines, including sink-tip lines and some of the faster-sinking intermediate lines may fall into this category as well).

I do the vast majority of my saltwater fishing with floating lines—much to the consternation of a number of guides with whom I’ve fished, as well as other anglers, many of whom have convinced themselves that a fish won’t move through several feet of water to feed (if this were actually true, the fish would starve). Floating lines cast and handle better than either intermediate or sinking lines, they are the best lines for learning how to cast, and the best choice to fish surface flies such as popping bugs, sliders, and hair-heads.

Intermediate lines have a density greater than water and sink at relatively slow rates, starting at about one inch per second. Keep in mind that sink rates are determined under laboratory conditions in still water. The sink rate of an intermediate line might differ significantly in actual use, particularly when you figure current and retrieve into the calculation. In practical terms, intermediate lines are perhaps best used to get the line just beneath the water’s surface, where it will be less affected by wind and wave action, giving you a better connection to the fly than would a floating line in the same environment.

Intermediate lines have a density greater than water and sink at relatively slow rates, starting at about one inch per second. Keep in mind that sink rates are determined under laboratory conditions in still water. The sink rate of an intermediate line might differ significantly in actual use, particularly when you figure current and retrieve into the calculation. In practical terms, intermediate lines are perhaps best used to get the line just beneath the water’s surface, where it will be less affected by wind and wave action, giving you a better connection to the fly than would a floating line in the same environment.

If you must reach fish that are holding deep you’ll need to use a high-density line. Many sinking lines on the market today are configured as integrated shooting heads–that is, a high-density head of 20 to 30 feet that transitions to a floating or intermediate running line (e.g., the Teeny lines first marketed in the early 1980s). Cortland’s Quick Descent series of lines are true sink-tips, with 15 feet of fast-sinking tip that transitions to a floating head and running line.

If you must reach fish that are holding deep you’ll need to use a high-density line. Many sinking lines on the market today are configured as integrated shooting heads–that is, a high-density head of 20 to 30 feet that transitions to a floating or intermediate running line (e.g., the Teeny lines first marketed in the early 1980s). Cortland’s Quick Descent series of lines are true sink-tips, with 15 feet of fast-sinking tip that transitions to a floating head and running line.

Depending on their density, sinking lines will sink at a rate of three inches per second to eight inches or more per second–your selection being determined by water column, current, and conditions.

Some boat anglers choose sinking lines even when targeting surface-feeding fish. For example, in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states many striped bass anglers will opt for sinking lines when casting to breaking schools with the idea of getting down beneath the more aggressive schoolies to get a shot at larger fish that may be holding below.