from the EDITOR

I always find it odd, writing these letters that won’t be read for several months. It feels like making a short-term time capsule. It’s mid-July, and fun to think about all the things that will have changed come mid-September when you read this. Yes, the leaves will have transformed to their autumnal glow, but we will also have changed. It happens every fall, as if on cue, usually on an almost-frosted morning: a feeling that springs from some deep and primal well inside us that signals the easy days of summer are over and hunting season has begun.

If all goes to plan (and you know about the best laid schemes of mice and men), I will have an elk in the freezer early this fall, and my focus will shift entirely to hunting birds with my pointers. It’s laughable to consider the difference between my current hunting plans and what the realities will likely be. I had the same plan last year, but after eating elk-tag soup spent the better part of October and November perched in a tree hunting deer. My dogs looked at me accusingly when I strolled back in after dark. When I finally did notch my deer tags, I was thankful both for the meat and for the opportunity to finally follow my dogs through the country, rather than stare at it from a stationary roost.

Sitting alone and waiting for a deer, I had plenty of time to daydream about the wonderful upland hunting to come: days filled with good dog work, beautiful country, and plenty of birds. Of course, that too was different from reality. The deluge of hunters trying to stay sane during the pandemic let me know my secret spots weren’t so secret anymore. There were a lot of last-minute audibles when I found other trucks already parked at my favorite spots, and I ended up hunting marginal places I hadn’t been before. Yet, I did get my wish: There was plenty of walking.

In the early 2000s, when quail numbers in my home state of Nebraska dropped to the point where you were just as likely to jump Bigfoot out of a hedgerow as a covey of quail, my dad became fond of saying he was “just going out for a walk” rather than going hunting. Still, even on days when birds seem to be everywhere, you spend 99 percent of the time walking, with trigger pulls only punctuating long stanzas of hoofing it. I was fortunate to experience the luxury of hunting atop a “quail rig” this past year, and I hope to someday take part in what I imagine to be the pure romanticism of hunting by horseback, but I am proud to be a lowly foot hunter at heart.

Walking is good for its own sake. It is exercise, yes, but I think real walking involves much more. I remember reading Thoreau’s Walking in college. “When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or mall?” he writes. “Give me a wildness whose glance no civilization can endure—as if we lived on the marrow of koodoos devoured raw…. Life consists with wildness. The most alive is the wildest…. All good things are wild and free.”

Thoreau didn’t hunt, but I suspect that was more due to the absence of deer from his 1840s Massachusetts than a disapproval of hunting. Even so, his writing gets to the heart of what I suppose we are really chasing as we follow our dogs through the countryside: to experience that ancient wildness that lies dormant inside us and the ecstatic feeling of being alive and connected to the world when a bird rockets into the air. Walking is part of that experience. To feel the ground flow past. To reach places that no road leads to. I know I’ve often looked around—whether it be at the top of a hill overlooking wrinkles of rolling prairie or some deep, tangled grouse woods cover— and wondered, How the hell did I get here? By foot, that’s how.

Thoreau’s real agenda in Walking is to “regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society,” and who is more part of nature than a hunter? Hunters aren’t mere observers; to borrow a phrase from the author Pete Dunne, they are actors taking part in an incredible drama on a world stage in which all living things play a part. The importance of walking, then, is that it reminds us that the pleasure of hunting comes more from the process than the product—that shooting a limit of birds is not important; going hunting is what’s important.

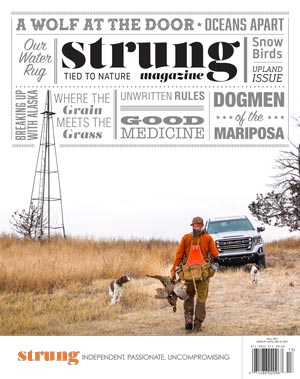

In this issue, Matt Wemple writes about appreciating the good times while they’re still good; Jim McLennan describes the pleasure of hunting Huns in southern Alberta; Tom Keer, Don Thomas, and Callum Macgregor write about the finer points of dog work; and Andrew McKean relates why you should never discipline someone else’s dog. Finally, Adam Tangsrud shows us the beauty of hunting late-season roosters in the snow. I hope these stories get you excited for your own upland seasons. Working on this issue has certainly fired me up. I’m ready for a walk.

Keep Casting,

Ryan Sparks

Editor-in-Chief

SUBSCRIBE TO STRUNG MAGAZINE